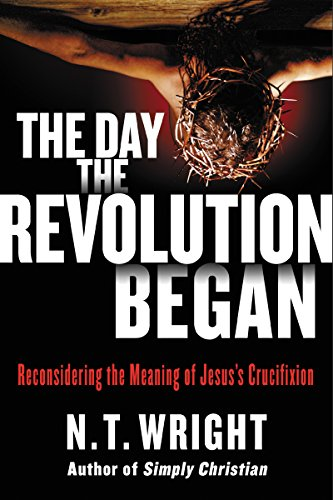

The Day the Revolution Began: Reconsidering the Meaning of Jesus's Crucifixion by N.T. Wright (Considered Heir of C.S. Lewis)

You can click the link above If you wish to own a copy or give it as a gift to your fellow brethren!

Christian Community and Editorial Reviews

Christian Community Review #1:

The Day the Revolution began is attempting to do the same type of analysis with our theology of the atonement. I assume that many of NT Wright’s traditional critics will also disapprove of this book. Wright’s minimization of Penal Substitution (which has been clear in much of Wright’s writing) is explicit here. Wright is not saying that Penal Substitution is wrong. He is saying that the focus on Penal Substitution as the primary or only way to look at the atonement distorts our understanding of what Jesus did on the Cross.

My traditional approach to Wright is to listen to the book on audiobook once, than re-read it again later in print. This allows me to get an overview of the argument and then to focus more clearly on the parts of the argument on the re-read. This is certainly a book that I am going to need to re-read to fully understand, maybe twice.

One of the reasons that many get irritated with Wright is that is keeps presenting his ideas as either new, or the first return to ‘correct’ understanding in hundreds of years. If you are irritated about that, you will be irritated here. Wright’s strength is connecting the broad narrative sweep of scripture and the 1st century era culture. I think if he started working with a historical theologian that helped him connect his ideas explicitly to the historical theological work of theologians after the first century, it would help tone down that irritating tic and help readers connect his thought to its historical roots.

Wright wants to help people think clearly about how their theology connects to their daily life. I think that is one of his strengths. But part of what the church today needs is a connection of its theology to the historical church. But his description of his work as either new, or a rediscovery of what is lost, minimizes the connection to the historical teaching of the church. This is particularly true for low church fans of his that do not already have a strong connection to the traditional church. Maybe this is a blind spot that Wright has because of his British Anglican setting. Wright himself has a strong sense of both history, and the world wide range of the church, but many of his readers (and biggest fans) do not. (My reading of Thomas Oden in particular has convinced me of the importance viewing the theology of the church as a continuum with historical teaching and not new.)

Like virtually all of Wright’s books, The Day the Revolution Began is impossible to easily summarize. The best I can do is to say that Wright is making the argument that the cross was not primarily about dealing with sin (although it did do that) but about fulfilling the covenantal promise to Israel. The cross shows that the kingdom of God, which Jesus was claiming at the cross, is fundamentally a different conception of power than earthly power structures. And that the cross isn’t about Jesus dying for our sins as individuals but more about Jesus dying in order deal with the corporate idolatry of Israel as illustrated by the prophets and draw the rest of the world into covenant with God.

The biggest indictment against modern theology that Wright is making in the Day the Revolution Began is that we have reduced the cross to the fulfillment of a ‘works contract’. Jesus paid the price of God’s anger toward our individual sin and died so that God would forget his anger. Again, Wright is not saying that there is not some truth to this view. But it is a partial truth. Jesus’ death was part of the plan from the beginning not a result of our sin.

This quote (about Galatians’ message) is a good example of Wright’s goal here. (He is trying to get us to look at the cross from a different angle to help us understand it better.)

"The letter is about unity: the fact that in the Messiah, particularly through his death, the one God has done what he promised Abraham all along. He has given him a single family in which believing Jews and believing Gentiles form one body. What Paul says about the cross in Galatians is all aimed toward this end: because of the cross, all believers are on the same footing. And if that is the “goal” of the cross in Galatians, we will gain a much better idea of the “means.” As elsewhere in this book, our task is to rescue the “goal” from Platonizing “going to heaven” interpretations and the “means” from paganizing “angry God punishing Jesus” interpretations—and so to transform the normal perception of what “atonement theology” might be from a dark and possibly unpleasant mystery to an energizing and highly relevant unveiling of truth."

In the end, Wright is not minimizing Jesus’ work by moving the focus away from individual sin redemption. Wright is working to expand our view of Jesus’ work to make it a much bigger things than just individual sin redemption.

One last quote:

"And that means what it means not because of a “works contract,” a celestial mechanism for transferring sins onto Jesus so that he can be punished and we can escape, but because of the “covenant of vocation”—Israel’s vocation, the human vocation, Jesus’s own vocation—in which the overflowing love, the love that made the sun and the stars, overflowed in love yet more in the coming to be of the truly human one, the Word made flesh, and then overflowed finally “to the uttermost” as he was lifted up on the cross to draw all people to himself."

Christian Community Review #2:

First off to explain my rating, it is a wonderful, albeit dense, read. I have a feeling that this is an important book in the series of N. T. Wright's popular authorship (e.g. Surprised by Hope, Simply Christian, How God Became King, among others). Here he undertakes an ambitious attempt to weave various strands of his original expositions set out on numerous occasions into the very epicenter of our Christian faith. The enormous emphasis he has vigorously and justifiably placed through his past publications on the so-called Jewish contexts SURROUNDING the cross is here leveraged for the purpose of DIRECTLY illuminating the meaning of Jesus' crucifixion. I kind of consider this book as his delving into the very core of his own theological framework, where he examines all his previous enlightening arguments (e.g. the meaning of resurrection, ascension and new creation, human vocation and creation narrative, the Gospels' accounts of God's kingship, Jesus' representative substitution, the significance of Israel's rugged history, the unity of the Church, the role of the Spirit, heaven-and-earth interplay, among countless others) against Christianity's overriding centrality of "what happened on the six o'clock of that Dark Friday." And he discovers that it actually makes breathtaking sense within his theological framework; the process of this discovery makes this book a fascinating read, especially for an avid reader of Wright as I am.

Now that was a lengthy one-paragraph comment to explain my five-star rating. I am actually writing the review in order to address the extreme polarity of ratings I currently observe. Even given the small sample size of seven ratings at the moment of my writing, 57% five-stars and 43% one-stars with no in-betweens certainly is not an ordinary pattern for any book, regardless of actual quality.

I think it is due to the fact that in this book, Wright sounds overly confrontative with the 'traditional' Protestant framework of understanding the crucifixion. Throughout the gradual buildup of arguments in the early parts of the book, he harshly belabors how the criticisms of his dissenters are missing the point. I understand his motivation since some people really will mount such oversimplified objections when he is at his crucial logical progression towards the climax. But even though I'm his fan, I still get the impression that he himself somehow repeatedly oversimplifies the 'traditional camp', especially Calvinist and Protestant formulations of Christian theology, that he differs with.

Excluding those grossly distorted angry-God-in-the-sky-sending-people-except-some-to-hell theologies that Wright, AND the traditional campers, rightly criticize, I have always felt that the issue arises more from the difference in approaches and emphases than from the degrees of theological validity. Wright, on one hand, enriches our Christian understandings with the highly needed historicity of the good news in multifarious layers and scales, spanning from Israel's stories all the way up to the cosmic narratives of creation and new creation. (I think that in this book, he shows that this multilayered historicity of the good news truly culminates squarely in the cross, much to many skeptics' relief.) The traditional Protestant perspectives, on the other hand, have had the philosophical underpinnings, addressing the fundamental relationship between the quintessentially human conditions and quintessentially divine providence that underlies the entire history. It is true that the traditional frameworks have had to undergo numerous improvements and corrective adjustments, but that does not prove their ultimate inadequacy at all.

I think the right theology has to possess both of these two pillars, covering the historical dimension of how the Bible weaves the story of God's initiatives in the world as well as the philosophical one of what it really means to us who are living in our own stories. The former complements the latter by, as Wright always masterfully suggests it does, inviting us to live our stories as part of God's, while the latter complements the former by filling God's story with the praises of people whose stories are personally (and yes, sometimes sentimentally) overwhelmed with his infinitely profound grace. They are mutually reinforcing, and definitely not at odds with each other.

For example, let me talk about the highly contentious imputation theology. I personally am more sympathetic to Wright's assertion that it is a caricature of the real thing. His alternative explanation of what it intends to convey seems to me to make more natural sense in the broader narratives of the Bible. I feel, however, that Wright's alternative somehow rids us of the feeling of overwhelming awe that we have when we realize that we are "put to right" (Wright's way of saying it) even though we have done nothing; that sense of personal significance is much better captured by the "imputed righteousness" account, even if it is indeed a caricature. I think the "Imputation" explanation delivers the sense of immense personal relevance at the cost of contextual simplification, while Wright's "Covenant membership" one conveys what that relevance really means in the grand scheme of God's world-saving plan at the expense of personal sensitivity, which does matter. In my humble opinion, it is much better if we retain both elements.

Personally speaking, while being a serial reader of N. T. Wright, I attend a church in South Korea where the main pastor, also a highly influential Christian author in my country, preaches from an utterly traditional Protestant framework. I sometimes find his understandings of grand historical undercurrents in the scriptures quite crude, and yet it is his sermons, not Wright's books and lectures on YouTube, that never fail to seriously challenge my personal faith and life towards more and more resolute obedience. At the same time, Wright has genuinely broadened my eyes to see God at work through the grand history of creation, and this is increasingly becoming a solid ground for my career aspirations (to somehow--I don't know how yet--implement Christ's victory in the greed-distorted fields of finance!), something my endeared pastor has not quite helped with. I am tremendously indebted to both trustees of God's Word, and I believe that they are both God's genuine theologians.

I write this review in order to contribute even just a little to promoting a reconciliatory conclusion for this unproductive controversy, where some critics nitpick Wright's every argument out of the understandable conservative fear that the essence of Christian faith might be at risk, and Wright in response becomes growingly defensive/accusative in his writing and ends up unduly caricaturing the differing perspectives, as he unfortunately does several times in this otherwise fantastic book. Here, Wright emphatically affirms the utter centrality of the cross and the forgiveness of sins, the two topics that he has not quite directly delved in before, and I do not think God would forbid him to work out their implications freshly onto the historical plain of the stories of Israel and humankind, rather than onto the already much-explored philosophical plain of intimately personal relevance.

Editorial Review:

“The question ‘Why did Jesus have to die?’ has haunted the human race for two thousand years. Wright locates the crucifixion in the sweep of Israel’s story (and ours) with power, depth, and freshness of thought.” (John Ortberg, senior pastor of Menlo Church and author of All The Places To Go)

“Many have wondered where N.T. Wright stood in the atonement debate. He applies his story of Israel and the church to the cross, setting it into a historical and narrative matrix that sheds light on the heart of the gospel that comes from the heart of God’s love.” (Scot McKnight, author of The King Jesus Gospel)

“Wright’s unwavering faith in the resurrection is quite evident as he defends the Easter narratives on historical and theological grounds.” (America Magazine)

“From the day Christ was crucified his followers have sought to understand the meaning of the cross. Wright has written one of the most important books on this subject ever written. Something deeper, more revolutionary, happened on the cross. This book will help you discover the meaning of the cross.” (Adam Hamilton, author of Making Sense of the Bible)

“Relevant Recommends: Wright invites us to explore the crucifixion within the broader story of what God is doing in creation” (Relevant)

“N. T. Wright’s The Challenge of Jesus revolutionized my theology. As I read The Day the Revolution Began, I kept thinking that it will similarly revolutionize the understanding of a new generation of readers. It is lucid, engaging, thorough, compelling, and profoundly important.” (Brian D. McLaren, author of We Make the Road By Walking)

“In his new book, Wright explains that Jesus’ death does more than just get us into heaven.” (Christianity Today)

“Wright’s bracing and thought-provoking exegesis should inform and encourage everyone concerned with Christianity’s continuing vitality.” (Booklist (Starred Review))

“Offers a comprehensive interpretation of Jesus’s sacrifice and its significance for the Christian Faith” (Publishers Weekly)

From the Back Cover

When Jesus of Nazareth died the horrible death of crucifixion at the hands of the Roman army, nobody thought him a hero. His movement was over. Nothing had changed. This was the sort of thing that Rome did best. Caesar was on his throne. Death, as usual, had the last word.

Except that in this case it didn’t. As Jesus’s followers looked back on that day, they came up with the shocking, scandalous, nonsensical claim that his death had launched a revolution. That by 6:00 p.m. on that dark Friday the world was a different place. They believed that with this event the one true God had suddenly and dramatically put into operation his plan for the rescue of the world. They saw it as the day the revolution began.”

Leading Bible scholar, Anglican bishop, and bestselling author N. T. Wright argues that the church has lost touch with the revolutionary nature of the cross. Most Christians have been taught a reduced message that the death of Jesus was all about “God saving me from my ‘sin’ so that I could ‘go to heaven.’” According to Wright, this version misconstrues why Jesus had to die, the nature of our sins, and what our mission is in the world today.

In his paradigm-shifting book Surprised by Hope, Wright showed that the Bible’s message is not that heaven is where we go in the future; rather, the Bible sees the primary movement as heaven coming down to earth, redeeming the world, beginning now. In this companion book, Wright shows how Christianity’s central story tells how this revolution began on a Friday afternoon two thousand years ago and continues now through the church’s work today. Wright seeks to wake up the church to its own story, to invite us to join in Jesus’s work of redeeming the world—to join his revolution.

You can click the link above If you wish to own a copy or give it as a gift to your fellow brethren!

Feel free to add comments below and if you wish to receive a regular updates of the latest Christian Books for FREE which is always on a limited time and avail the cheapest price available real time and reviews, please add your email address in the comments section below.

Thank you and God bless!